The first 48 hours of this years Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race reinforced the old adage that you can’t win yacht races, if you can’t finish them. The fleet enjoyed a short lived, downwind sleigh ride out of Sydney Harbour in 18-20 knots, to be hit on the nose with stiff southerlies and steep 3m seas from the ‘wind against current’ conditions as they turned south.

The 100 footers looked powerful, but fragile as they started to bury their noses in conditions that were set to worsen overnight. Within minutes, the staysail furler of Scallywag tore off the deck with the sail and furler flailing wildly behind the main. I held my breath as I watched the skipper bear away to depower the situation and the crew member at the mast who dodged the furler that had now turned into a wrecking ball, swing past him at head level several times as he tried to secured the base of the 100kg+ sail to get it down onto the deck.

I was impressed by what happened next. Instead of retiring from the race as these grand prix machines seem to do more often than not, (from problems that are fixable, if you have the right tools and spares onboard) they simply got the boat under control and carried on sailing.

Black Jack takes 2021 line honours in the slowest race since 2004

It was great to watch the small army that descended on the foredeck to wrestle the staysail down onto the deck and hoist the storm jib in its place, to maximise boat speed while a repair was completed. At this level, its easy to assume that its all over if you are underpowered, but Scallywag hung in there, staying within 3-4nm of Black Jack and Law Connect, despite the setback and temporary speed loss.

I awoke the next two mornings to news of 35+ retirements, with most from damage to rigging or mainsails. Despite the conditions forecast at 30 knots, you can bet some of the crews saw 40 knots and maybe closer to 50 in the cold, wet conditions. It’s easy from an armchair to assume some of these yachts were underprepared to have exited so early, but the shock-loading on hulls and rigs in strong ‘wind against current’ conditions, from the constant pounding and crash landings that occur, when you fall off the back of hollow waves, should not be under estimated.

The pounding is hard on stomachs too and its easy to become airborne, when working forward of the mast as the foredeck disappears from underneath you. Any skipper that retires from a race in these conditions, to put the welfare of their yacht and crew first, is a great leader. It takes guts to retire when you have spent so much time and money to get to the start line, but it’s better to live to fight another day.

I salute every Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race skipper that gets their vessel safely back to port (wherever that may be) and their crew’s home to their families. Thats a successful result and for those that fell short of the finish line, there’s always next year.

Good luck to the crew of B52 from the Southport Yacht Club that are in the final 12nm of the Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race and leading their PHS division by the slimmest of margins when I checked this morning.

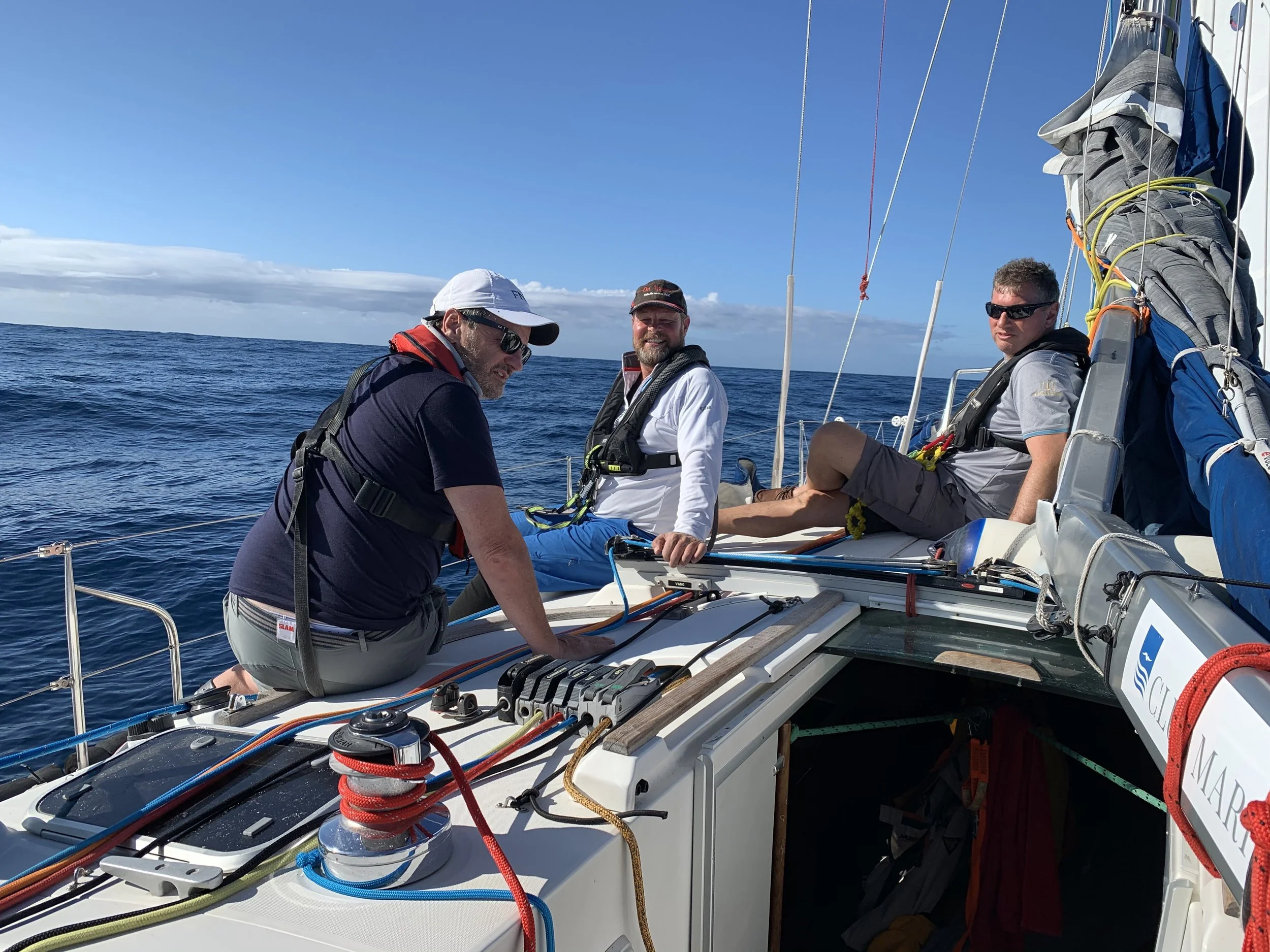

The Ocean Gem Crew complete the 2017 Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race

I have personally completed more than 600 races, regattas, passages and expeditions during the past 10 years and there have been 3 occasions I have retired from a race. In more than 100 of those events though, we have damaged gear, torn sails or had mechanical break-downs and had to improvise and make repairs in order to carry on. Its always a trade off between how many tools and spares you carry and how much space and weight you take up on board.

On my last yacht ‘Ocean Gem’, we carried tools and spares that probably added 200kg in weight. On Silver Fern we have more space, weight is less of an issue and we end up in some pretty remote places. The spare parts and tools we carry weight at least 500kg and take up 4 cupboards, 12 bins and 15 drawers and lockers.

Breakages are always disappointing (and sometimes expensive) but there is something deeply satisfying about working together as a crew and overcoming unexpected challenges, especially in difficult conditions. I have been in many situations where it’s taken a total team effort to brainstorm a plan and then execute the solution. In a funny kind of way it really makes a passage or race more memorable, when you have to overcome difficulty to get to the finish line.

I recently crossed the Tasman twice and circumnavigated New Zealand’s South Island and on all three trips, we experienced winds exceeding 50 knots and 4-7m seas. We also dodged squalls that we picked up on our radar that were moving at between 60 and 106 knots. On each occasion 25-38 was the maximum wind forecast. As the planet heats up, we appear to be experiencing more extreme weather and in the past 2 years, I have experienced gusts (not average wind) at 2-3 times what was forecast, plenty of times.

So whats the point I’m trying to make?

There’s a few points really and watching the Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race got me thinking about a few thoughts I’d like to share.

If you head offshore, don’t plan for the weather forecast, plan for the worst

The best plan considers all options. Weather changes, forecasts can’t cover every localised scenario and sometimes its takes longer than you expect, to get to your destination. Most people don’t plan to end up in extreme weather, but it hits all of us eventually if we spend enough time at sea. Mother nature does not care how experienced you are.Learn lessons from others

Before I crossed the Tasman for the first time in 2013, I read every sailing tragedy and disaster book I could get my hands on and I made a lot of notes. The cheapest lessons you’ll ever learn are from the set-backs other sailors experience. I sail a lot of miles, so I break more than most. I share my experiences, so that you can apply my lessons to your situation. Sailing is fairly timeless. Lessons from 50 years ago are also still relevant today.Assume no one’s coming to save you

Assume you need plan B, C & D as well. Being rescued is overrated! No disrespect to the fine people you give up their time and risk their lives to save us at sea, but being rescued is not always easy or safe and help is not always near by. In heavy weather; getting into a life raft, undertaking a tow, getting alongside another vessel (especially a cargo ship) or getting into the ocean and swimming is fraught with risks. When you assume you have to get yourself to a safe port without help, you have a different mindset and that’s important. When you assume you have to get yourself home without assistance, the brain of each crew member works overtime thinking about solutions. When you are ‘out of options’, you figure out new options, you did not realise you have. They are not always immediately obvious, but with tools, spares and good leadership it’s amazing what you can create, as a team.Ask for help

Good leaders know when to ask for help. Being an expert does not mean you have all the answers either. You’ll be surprised how willing people are to help if you just ask. Your family, your crew, fellow yachties, trades people you can message via sat phone for advice, the coastguard, nearby marinas and commercial ships are all ready and willing to offer ideas, advice and assistance. You have to constantly assess the risk and chance of getting home safely, if the weather and your ability to manage the vessel is deteriorating. Make the call early while there is still time to plan and save the vessel and the crew.

Don’t wait for a Mayday situation when you can make a Pan Pan call earlier instead. In March 2020 we lost steering in Cook Strait, New Zealand at 9pm in 20 knots and 3-4m seas. We calculated we had 7 hours until the current would sweep us onto rocks. We called for help early so there was time to organise a tow. It took 5 hours to finalise a tow and a further 5 hours until it arrived. Luckily we figure out how to sail away from trouble, with no rudder and bought ourselves more sea room. Asking for help is an ‘ego issue’ for some skippers, who turn it into personal failure. Park your ego - getting home safely is far more important and better seamanship too. If you spend enough time at sea, you will need help eventually. I have had to request help more times in the last 12 months than the previous 10 years put together.

Fix it once, fix it forever

Some people get upset about breaking stuff. When you go to sea, it’s part of the process. The common thing to do is simply order the replacement part, fit it and carry on. I don’t recommend that. Grab it as an opportunity to work out why it really failed, because the same part will fail again, if you repeat the same set of circumstances.

Great seamanship and a touch of humour after the loss of steering from a broken steering cable and resultant crash gybe, causes broken boom in 20 knots. We were half way across the Tasman and 500nm from NZ so we rigged up the emergency tiller with a No.4 jib only hitting top speeds of 14 knots surfing in 4-5m seas with only 2 x 6mm lines to control the steering.

Ask yourself;

Why did it break or fail?

Was it really up to the task?

Do you need to upgrade or change how its set up, to stop it happening again?

Was it serviced at the frequency recommended by the manufacturer?

Did lack of training lead to the damage?

What can you do to fix this forever?. How do you fix this so that it never happens again.

With a little bit of thought and technical advice, you’ll be amazed how much you can improve the reliability of your yacht over time. Unfortunately you have to go through the cycle and work your way through a new yacht from end to end, until you eventually understand how each part works and the role it plays in the operation of your vessel.

When I purchased my Beneteau 45; ‘Ocean Gem’ in 2011, rewired her in 2013, added carbon sails in 2015 and was using the yacht 90+ times a year, I found all the “dark corners”. My continued investment in my “fix it forever” mentality, turned it into an incredibly reliable yacht, that along with spare parts and tools, meant it could overcome almost every set back. Sometimes we won trophies for ocean races simply because we made it to the finish, when 60% of the fleet had retired with damage and injuries.

With Silver Fern, the 72 foot yacht I have owned for 18 months now, I am about 80% of my way through the “fix it forever” process. It has more complex systems, bigger loads and it has been a steep learning curve for me, but my confidence is increasing as I work my way through this beautiful vessel. When I think about reliability and success, I ask myself - how many times did I get the vessel and the crew safely to the destination? My answer today is still 100%.

Some people assume break downs and damage are some sort of measure of failure or a vessel reliability issue. I don’t. My thinking is, I am sailing a vessel with 1,000+ moving parts, tools and spares onboard, through this weather, with a brand new crew, with all sorts of resources and information available to help me achieve this.

My measure of success is;

Did we enjoy the passage and work together well?

Did we get the yacht there safely?

Would this crew sail with me again?

Thats as complicated as it is for me. Breaking stuff is part of the process. Just don’t keep breaking the same stuff.

Don’t overthink it, go sailing

My last 2 sailing adventures included a South Island, New Zealand Circumnavigation and a Tasman Sea Crossing from Picton to Southport. In both events we experienced more wind than was forecast and had to contend with breakdowns and gear failure. My philosophy in life is “It’s not what happens to you, it’s how you choose to respond”. The most powerful word is “choose” because there are always choices and options. I get frustrated and disappointed like anyone else when things don’t go to plan and the large repair bills pile up as things break.

To to put the icing on the cake, I had 2 people contact me recently suggesting I was "reckless, ill prepared and should not be heading to sea in an unreliable yacht and putting peoples lives at risk”. Now - I am reasonably thick-skinned, but some of these types of comments make me stop and think about what I am doing and its easy to start overthinking.

Here’s the thing… 99.9% of the population will never sail offshore and out of sight of land. Some of the comments I get are from inshore (armchair) experts and while its good to listen to feedback, you can’t just give advice from a text-book. If you do enough miles in heavy conditions, everything gets tested. If you buy an older boat there are always things coming to the end of their life that need replacing.

When you head to sea, your goal is to; ‘mode your vessel for the conditions you find yourself in’. The weather you get does not always match the forecast and the wind gusts/squalls can be 2-3 times stronger than forecast. Know what your ‘go to’ mode is for 30, 40, 50 and 60+ knots. Think about chafe and loads on rigging, winches and sheets. Don’t undersize heavy weather gear, its a success or fail outcome. It works or it breaks. When it breaks, people can get hurt or put in harms way trying to clean the mess up.

You will never truly be confident in these conditions if you don’t experience them. Heavy weather sailing can be scary and exhilarating at the same time. When you head to sea, you are putting your life in your vessels hands and hoping like hell that Mother Nature is kind to you.

Running aground at Fraser Island and replacing 8m of black water hose after the toilet blocks up, on a passage north to Hamilton Island in 2021

“The good sailors get the good luck”

I read that quote more than 30 years ago and its proved true so many times. Training, preparation, seamanship and leadership is a choice, it does not happen by chance. If you prepare your vessel well and train your crew, you will have a plan B and a plan C and you will return safely to land. Every sailing tragedy I have ever read about was never a result of ‘bad luck’. In every story there are multiple things (in hindsight) that the sailors could have done differently, that would have saved them and their vessel. Most of them relate to vessel preparation and use of safety equipment.

When you head to sea, you take a leap of faith. I remember leaving Hobart in 2018 to cross the Tasman Sea solo for the first time on Ocean Gem. On night two the wind changed from SW at 20 knots to NE winds at 30 knots and the two opposing swells created a washing machine for the next 24 hours. I lay in my bunk at 2am with Ocean Gem on autopilot and no matter what direction we steered, we fell off every 10th wave and crashed 3-4m into the dark ocean below. The hull crashed, the rig shook, the cupboard doors rattled and the cutlery in the drawers jingled. I lay there thinking how difficult it would be to get into the life raft if the hull broke in half or keel broke off. I knew I would die of hyperthermia without being in the raft as I was already out of helicopter range.

I remember being scared as my mind over analysed all of the scenarios. Then logic kicked in; “ I have a strong boat, it's well built, I have new rigging, I have trained, I am prepared”. Something strange happened that night. I decided to accept my fate and just trust the outcome. I decided; “if this is how it ends, then so be it”.

I made it safely across the Tasman Sea and have now crossed it 11 times in total. Since that night, I’ve found it easier to work through difficult situations and heavy weather. Being ‘scared’ is okay, because it makes you cautious and ensures you double check everything, so that your fear subsides. ‘Worry’ however is an emotion that offers no value. It fills up your mind and will often paralyse you into ‘inaction’. Not acting when you should is dangerous. Time is a major asset at sea. Get your vessel and crew ready early and heavy weather is exhilarating. Wait until its on top of you and heavy weather is dangerous and can result in your crew getting injured and your vessel being overwhelmed by the ocean and wind.

It's all about timing. Same crew, same vessel, different outcome - timing is the variable. Checklists, teamwork, acting on your instincts and being conservative are keys to getting through heavy weather. Depower the rig, reduce loads on the boat, go for comfort, mode your vessel to be in harmony with Mother Nature, don’t fight her - “the good sailors get the good luck".

Its experience that builds your character and gives you judgement. The magic happens when you go sailing. Happy 2022!